So, why are the Dutch looked up to as an example not only when it comes to handling environmental issues, but economic ones as well? The answer lies in the ‘polder model’, one that values consensus and cooperation rather than confrontation, with deep historical roots that have created the foundation for a cultural tradition. The Dutch identification with this consensus-building model is what lies behind much successful policy in Amsterdam, specifically in themes elaborated on throughout this blog. As the Netherlands is densely populated and has issues of heavy pollution from chemical industries, oil refineries, international transportation and intensive agriculture, the polder model emphasizes finding a solution between actors that may otherwise have conflicting goals in the name of a larger issue (Schreuder, 2001).

In Amsterdam, the five key aspects of the polder model visibly present within the city’s governance are: mutual commitment, joint fact-finding (so decisions are grounded in rigorous research), compromise, priority alignment (avoiding irrelevant subjects), and balance between centralization and decentralization (Karsten et al, 2008).

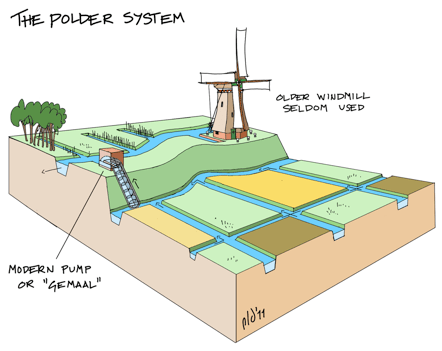

However, we must go back to the Middle Ages to understand where the “polder model” comes from, and what it represents. Back then, the polder was an important feature of the Dutch landscape. It was land reclaimed from water that was protected by dikes against flooding. They were difficult to build and to maintain, requiring plenty of manpower and capital. The Catholic church initially had their monasteries control these polders. Once the Church lost power in the country, the regulation was taken over by local communities (ibid). The polder boards, where principles of self-rule prevailed, resisted against Habsburg king Charles V in the 16th century, and were a large part of what led to the Eighty Years War (Schama, 1988). The tradition of Dutch cooperation and determination to overcome hardship was further solidified in historical events such as the German occupation of WWII and the flood of 1953.

In 1982, the Wassenaar accord was part of the revitalisation of corporatism in which there was an agreement between capital, labor and government to address issues based on the consensus building concept of the polder model. This has also extended into Dutch environmental policy, where, as problems are identified and a threat is widely recognized, stakeholders such as the municipality, entrepreneurs, civilians, and public authorities participate in finding a solution and implementing policy to address the concern (Schreuder 2001).

Amsterdam as its own municipality is charged with execution of national environmental policy, subject to creating new environmental and water management plans every four years. The city of Amsterdam seeks consensus through constructive dialogue which portrays a particular institutional system, or business system. Frequent and informal contact between stakeholders makes this process easier: especially in an urban setting in a country where environmental issues such as rising sea levels are particularly extreme.

Word Count: 467

References

Hoek, Peter. Does the dutch model really exist?. International Advances in Economic Research 6, 387–403 (2000)

Karsten, L., van Veen, K. and van Wulfften Palthe, A. (2008) ‘What Happened to the Popularity of the Polder Model?: Emergence and Disappearance of a Political Fashion’, International Sociology, 23(1), pp. 35–65

OECD (2014), Water Governance in the Netherlands: Fit for the Future?, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing.

Schreuder, Y. (2001) ‘The Polder Model in Dutch Economic and Environmental Planning’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 21(4), pp. 237–245