In a city as deeply associated with water as Amsterdam, water management is a particularly important theme to analyze within urban political ecology. Especially in terms of municipal goals to become ‘circular’, which focus on effective use of resources such as raw materials, energy and water (van der Hoek, 2017). Despite the epistemological divide between material culture studies and ecological anthropology, thinking in terms of urban metabolism allows us to see the ‘big picture’ quantification of inputs, outputs, and storage of energy, water, nutrients, materials and wastes in an urban region (Ingold, 2012). Employing the UPE lens we look at the flows of water, not just as standstill and fixed in place (Amin and Thrift 2002). This way of thinking is essential to the circularity of the city.

A rich history of water management and an ongoing fight of flood prevention, or sea intrusion, are at the essence of Dutch tradition and culture (Schreuder, 2001). Currently, the Netherlands is a world leader when it comes to water management. Regional and local authorities combine duties with stakeholders, in the distinctive polder approach explained in a previous blog post (click here to read), emphasizing consensus-based decision making (OECD, 2014). Agudelo-Vera et al. (2012) quantified the potentials to harvest water and energy for the Netherlands and concluded that potentials can cover up to 100% of electricity demand, 55% of heat demand and 52% of tap water demand. Therefore, this blog post will focus on Amsterdam’s water cycle, and what is being done to maximise its sustainability.

“We do not only consult with other municipalities and public authorities. We also talk to civilians and entrepreneurs. Together we ensure a safe, clean and sufficient supply of water.”

Waternet, 2020

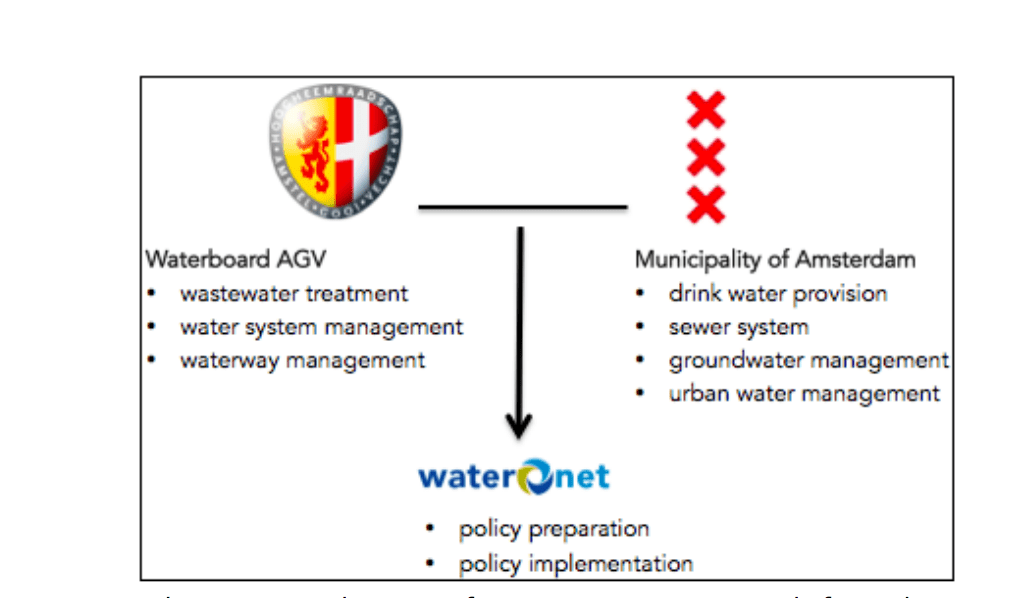

Waternet, the first water cycle company in the country, is responsible for drinking water treatment and distribution, wastewater collection and treatment, and water system management (canals, flooding) in Amsterdam (van der Hoek, 2011). It is the executive body of water management in the city, half coordinated by the municipality, and the other half by Waterboard of Amstel, Gooi and Vecht (AGV); the latter in charge of practices regarding wastewater (see Figure 1). The company wants to be climate neutral by 2020 through reduction of greenhouse gases and one of its primary goals is to recover resources from wastewater (Klaversma et al, 2013). Matters of wastewater are not under municipal authority, however, this goal still aligns with government aims of a transition to a circular economy.

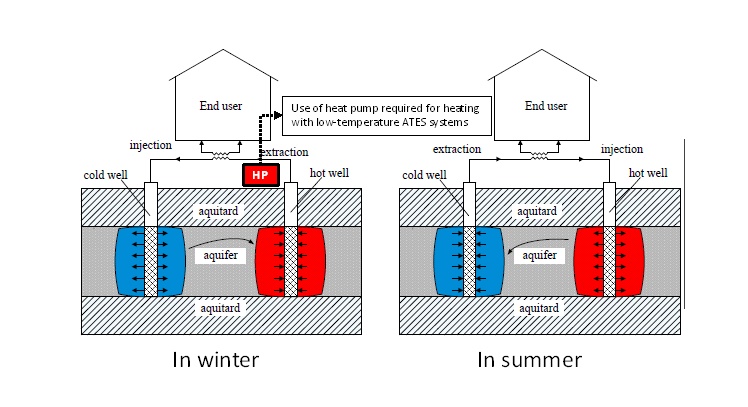

Waternet and the municipality have worked together on finding innovative opportunities for sustainable phosphate recovery. Phosphate is a non-substitutable nutrient essential to ensuring universal food security with its fertilization properties for agriculture (Sikosana, 2015). So far, the company has begun to enact a phosphate recovery plan that includes transforming the chemical into struvite, but they believe there are better methods that would reduce carbon emissions more substantially (De Jong, 2017). They have been busy creating a system in which energy recovery from surface water can be extracted as thermal energy, by using lakes as ‘cooling machines’, specific to the city in the summer (van der Hoek, 2011). Waternet had 80 projects installed or in construction in 2011 regarding energy recovery from groundwater, which amalgamated to an emission reduction of more than 23,000 ton Co2 at the time (ibid). Aquifer Thermal Energy storage (ATES) is used all throughout the city, as per environmental policy (picture below depicts how the system works). The potential energy recovery from the water cycle in Amsterdam can contribute 5% of the 40% reduction the city aimed for by 2025 (ibid).

AEB Waste-to-energy is another municipal company, in charge of two waste-energy plants in the city, and responsible for the collection and reuse of hazardous waste (van der Hoek, 2017). They have started to transition from waste incinerator to a sustainable energy and raw materials company.

The city of Amsterdam, alongside these companies, follows Venkatesh et al’s (2014) ‘Dynamic Metabolism Model’ and Agudela-Vera et al’s (2012) ‘Urban Harvesting Concept’. The former refers to a new perspective when analyzing metabolism and the ecological impacts of ‘resource flows in urban water and wastewater systems’, as a tool for future strategies and interventions (van der Hoek et al, 2017). The latter allows us to think of cities as consumers of goods and services, as well as producers of waste and therefore can be transformed to be more resilient by producing their own renewable energy and harvesting internal resources (ibid). Both these mechanisms are used by stakeholders and the municipality to achieve their own, and joint goals in the name of sustainability in Amsterdam. Thinking about the flows of materials creates opportunities not only ecologically, but economically as well.

Word count: 777

References

Amin A and Thrift N J (2002) Cities: Rethinking the Urban. Cambridge: Polity Press

Agudelo-Vera, C.M., et al., (2012) Harvesting urban resources towards more resilient cities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 64, 3–12.

De Jong, R. (2017) Governance of Phosphate Recovery from Wastewater in Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam

Ingold, T. (2012) ‘Toward an ecology of materials’. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 427–442.

Klaversma, E., van der Helm, A., Kappelhof, J. (2013) The use of life cycle assessment for evaluating the sustainability of the Amsterdam water cycle. Journal of Water and Climate Change 4 (2): 103–109

Sikosana, M. (2015) A technological, economic and social exploration of phosphate recovery from centralised sewage treatment in a transitioning economy context. University of Cape Town.

Schreuder, Y. (2001) ‘The Polder Model in Dutch Economic and Environmental Planning’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 21(4), pp. 237–245

van der Hoek, J. (2011) Energy from the water cycle: a promising combination to operate climate neutral. Water Practice and Technology 6 (2)

van der Hoek, J., Struker, A. & de Danschutter, J. (2017) Amsterdam as a sustainable European metropolis: integration of water, energy and material flows, Urban Water Journal, 14:1, 61-68,

Venkatesh, G., Sægrov, S., and Brattebø, H., (2014) Dynamic metabolism modelling of urban water services – Demonstrating effectiveness as a decision-support tool for Oslo, Norway. Water Research, 61, 19–33.

Waternet. Accessed on 3/5/2020. Retrieved from: https://www.waternet.nl/en/about-us/who-we-are/

One thought on “Waternet and Amsterdam’s Municipality: teamwork makes the dream work”