10cm is the average amount of rainfall experienced in Las Vegas annually, making it highly vulnerable to water shortages (Lasserre, 2015). In the early 1990s it was thought that with the current rate of population growth that Las Vegas only had 6 years before it became a water deficient city (Gerlak & Soden, 1992). Thankfully this has not yet happened. In this blog post I will examine the threat of water shortage in Las Vegas and what has been done to avert this.

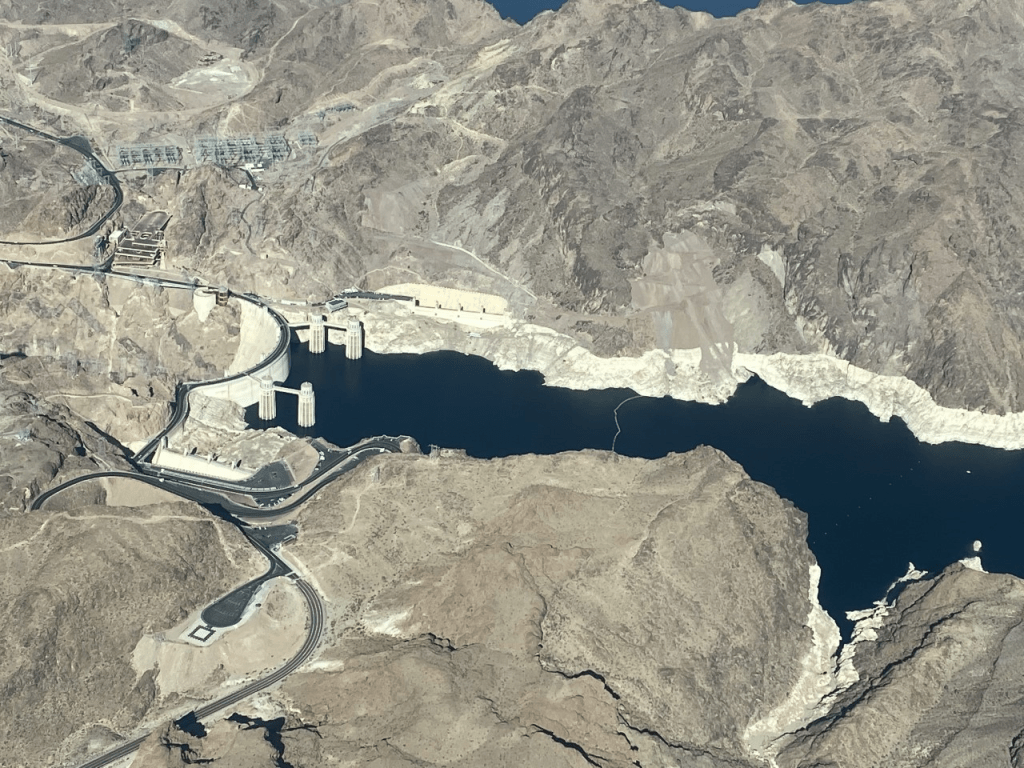

Las Vegas draws 90% of its water supply from the Colorado River – the water is collected at Lake Mead – this then supplies the population (Rothberg, 2017). The Colorado River is an over-allocated resource with other states also being largely supplied by the river. The River has been in a period of drought since 2000 (which is thought to be the worst over 1250 years – from tree ring data) (Robbins, 2019). This drought coupled with increased evaporation due to climate change has meant that the Colorado River has more water promised to users than is actually available (Robbins, 2019).

With the Las Vegas strip showcasing bountiful lush gardens, showstopping fountains and numerous water features, it is often assumed that the hotels and casino are responsible for the depletion of the water. This is wrong, in fact, only 7% of water use is by the hotels and tourists. Due to efficient water collection and recycling, A staggering 60% of water use is actually by the homeowners in residential areas of the city (Lasserre, 2015)!

The population of Las Vegas has grown considerably since the 1970s, from 227,000 people to over 2million (incl. surrounding outer city suburbs). This has meant that household demand for water has increased. State officials caught wind of this before it was too late and implemented policies to reduce per-capita outdoor water use. Schemes such as offering financial incentives for people to remove their front lawn, coupons and discounts to any individuals using water saving tech – such as pool covers or low flow toilets and laws to restrict car washing and back-yard lawn watering were used (Lasserre, 2015). These worked to reduce per capita water consumption from 350 gallons per day to 212 gallons (1989-2013 respectively) (Lasserre, 2015). Little has been done to reduce indoor waste usage as thanks to an extensive drainage network, a large proportion of the water used is able to be treated and returned to Lake Mead for use once again – a process of urban metabolism (Gandy, 2004).

After being predicted to become water deficient before the millennium Las Vegas has continued to supply its residents successfully. Climate change puts further strain on resources so alternatives do need to be considered. The Southern Nevada Water Authority are lobbying for a 250 mile pipeline to pump groundwater to compliment water supply from the Colorado River (Rothberg, 2019). Although there are concerns that this would alter the ecosystem, and that the groundwater may be contaminated with radioactive material. Objections to this have come from local tribes – who would be removed from their land and environmental groups. Other alternatives include desalination of ocean water – this could be undertaken in California – who are another key user of the Colorado River. By desalinating ocean water less demand would be being put on the Colorado River. Argument for either of these alternatives comes from the potential economic benefit that it would bring. It is unlikely that development in Las Vegas would continue at such a rate if developers thought the area may not be able to cope with the added populations, therefore ‘new’ water sources need to be found (Rothberg, 2017).

So far policy at the local scale has been very successful in reducing demand on the limited supply. This shows how using financial incentives alongside law creation can help urban populations conserve finite resources. Long term alternatives that involve large scale infrastructure are often met with fierce opposition – as is this case with the pipeline options. Officials and Water suppliers argue that they are using the alternatives as a precaution to future populations and to foster future economic development.

Word Count: 684

References:

Gandy, M. (2004). “Rethinking urban metabolism: water, space and the modern city.” City 8(3): 363-379

Gerlak, A. & L. Soden, (1992) Political culture and water politics in Nevada: Las Vegas attempts to quench its thirsts, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Lasserre, F (2015) Water in Las Vegas: coping with scarcity, financial and cultural constraints. City, Territory and Architecture, 2(1), 1–11.

Robbins, J. (2019) The West’s great river hits its limits: Will the Colorado River run dry, (WWW) YaleE360: Connecticut (https://e360.yale.edu/features/the-wests-great-river-hits-its-limits-will-the-colorado-run-dry, last accessed 31/03/20)

Rothberg, D. (2017) Why Southern Nevada is fighting to build a 250-mile water pipeline, (WWW) Water Deeply: New York (https://www.newsdeeply.com/water/articles/2017/10/12/why-southern-nevada-is-fighting-to-build-a-250-mile-water-pipeline, last accessed 31/03/20)

Further reading:

Page, B. (2005). “Paying for water and the geography of commodities.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 30(3): 293-306.

Cousins, J. (2017) Structuring hydrosocial relations in urban water governance, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107: 5, 1144-1161

Intriguing read on water in Vegas and the use of the Colorado River. Points raised about how economic incentives drove change on a individualistic scale were interesting, and highlighted how trying to create change has to be via a reward for the individual, a characteristic of Western culture.

The section about ecological damage from over-withdrawing from the River is also interesting, and it would be good to see to what end-point the damages occur before serious action is taken place, and by whom, at what financial cost and who does it benefit/impact the most.

As you’ve stated, tribes and minorities often put up resistance against decisions being made as they are the ones being disproportionately being impacted. Policy typically ignores their voice or puts them much further down the list. I’ve often found the same throughout my blog posts on Toronto, particularly in the air pollution and waste posts for example.

LikeLiked by 1 person