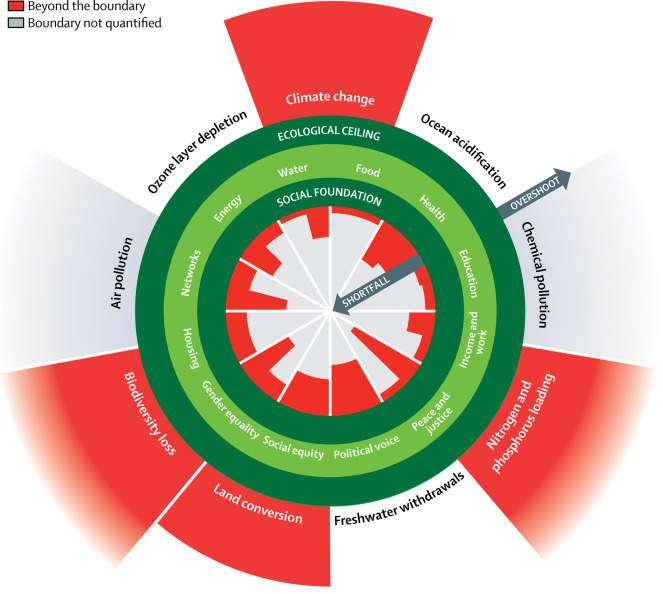

Kate Raworth, from Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, created a new economic model, based on a shifted attitude of economics: one that aims to find an equilibrium between social and ecological factors encompassing humanity’s well-being. Instead of emphasizing the current linear goal of a never-ending GDP growth, this conceptual framework of social and planetary boundaries creates a shape similar to a doughnut (Raworth, 2017). The inner boundary represents a social foundation, with twelve dimensions based on the internationally agreed standards of 2015 Sustainable Development Goals by the UN. The outer boundary is an ecological ceiling beyond which lies an overshoot of pressure on the planet’s life supporting systems. As, under current policy, millions of people’s lives fall short of the social standards of nutrition, health care, housing, income, etc., and human activity has overshot at least four planetary boundaries, Raworth (2017) created this compass to emphasize thriving in balance over endless growth.

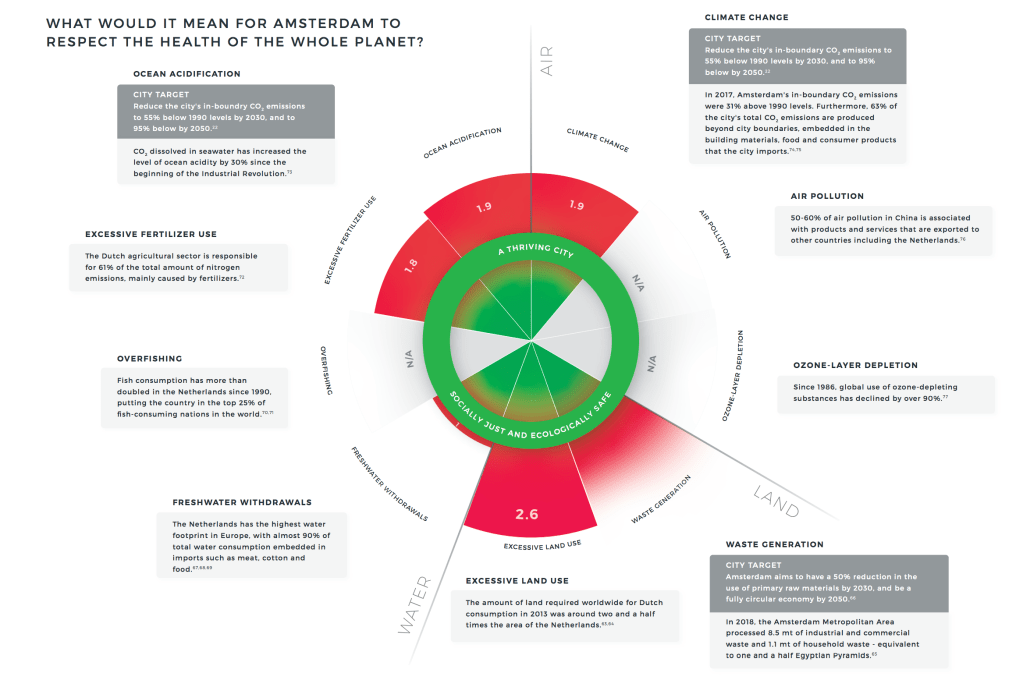

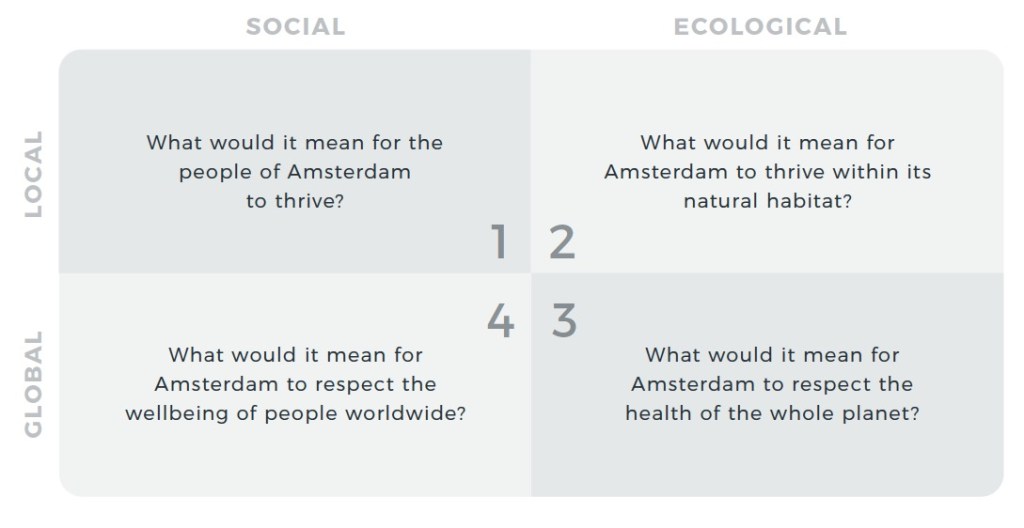

Amsterdam recently announced its commitment to the doughnut model to rebuild the city’s economy after the Covid-19 crisis, being the first city in the world to do so. Municipality officials met with Raworth to create a city-scale of this circular economy, and formally embraced it as the starting point for all public policy decisions. The doughnut grants a framework to think about climate, health, jobs, housing, care and communities simultaneously.

“We are looking at our economy in a completely different way: how we produce, process and consume.”

(City of Amsterdam)

The city plans on being completely circular by 2050, based on reusing raw materials to avoid waste and reduce Co2 emissions. For example, its new vision includes lengthening the life of materials by emphasizing repairing and sharing instead of throwing away, and having the port completely independent of fossil fuels. The municipality has already begun to create monitoring tools to track and trace raw materials, and also aims to cut food waste in half by 2030, rerouting surplus to residents in most need (Wray, 2020). Construction tenders will have stricter requirements of sustainability, and buildings will have ‘passports’ noting materials that may still be valuable or recycled upon demolition, such as insulation, timber frames, bitumen, doors, metals and stone (Report 2019). The municipality has already begun working with businesses and research organisations on over 200 circular economy projects (Edel, 2020).

The doughnut helps look at how things are interlinked, granting you a bigger picture of issues. It shows the economy not as the neoliberal story of a self-contained market, but as one that is embedded, emphasizing its dependence on society and the living world (Raworth,2017). It extends the metaphor of urban metabolism past the plane of raw materials, and into society. It also allows a shift in the perception of human nature to social, adaptable and interdependent beings embedded within the ecosystem (ibid). The model employs the economy as a series of dynamic complex networks, and not one that must adhere to an imagined mechanical equilibrium of the market. Of course, this sort of paradigm shift is no easy task. It seems that Amsterdam has to change the mentality of all its citizens away from a ‘capitalist imaginary of endless economic growth’ and into one that is more UPE style focused on flows and processes (Wright and Nyberg 2014:206).

‘The coffee I sip connects me to the conditions of peasants in Columbia or Tanzania … to climates and plants, pesticides and technologies, traders and merchants, shippers and bankers, bosses and workers.’ (Swingedouw and Kaika, 2008:568)

Furthermore, this model provides a space to talk about issues that were previously shrouded in importation and production. It links a product to the processes that made it possible for your consumption: a perfect tool for UPE. For example, the Port of Amsterdam is the world’s single largest importer of cocoa beans. These are usually imported from West Africa, where labour is often highly exploitative (Raworth et al, 2020). The value of this model, says Raworth, is that it enables a conversation shift about Amsterdam which includes labour rights in, as per this example, West Africa. It grants you the tools to question whether you want your city to be a place that condones this type of exploitation on a global scale (Boffey 2020).

Of course, this shift does not come without friction. As pioneers of the urban doughnut model, the city of Amsterdam is aware that the future is uncertain (Wray, 2020). Experimentation and acceptance of risk must be acknowledged by society, and together the city must break old habits. Many benefits may not be noticeable straight away, or they may not even occur in the city itself. Sometimes, the benefits could occur on the other side of the world. But Amsterdam’s policy makers believe the city is progressive enough and liberal enough to stand up to the challenge and invest in the future by protecting people, and the planet.

Word count: 808

References

Boffey, D. (2020) “Amsterdam to embrace ‘doughnut’ model to mend post-coronavirus economy” The Guardian. Retrieved at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/08/amsterdam-doughnut-model-mend-post-coronavirus-economy#maincontent

Edel, D. (2020) “Amsterdam is the First City to Implement the Doughnut Economic Model” Intelligent Living. Retrieved at: https://www.intelligentliving.co/amsterdam-doughnut-economic-model/

Hill, J. 2020 Floating renewable battery launched to recharge boats in Amsterdam, The Drive.

Raworth, K. (2017) A Doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st century The Lancet Vol 1(2) pp. 248-e49

Raworth, K. (2017) Why it’s time for Doughnut Economics IPPR Progressive Review Vol24(3) pp. 216-222

Raworth, K., et al (2020) Report: The Amsterdam City Doughnut (A Tool for Transformative Action), Retrieved at: https://www.kateraworth.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200406-AMS-portrait-EN-Single-page-web-420x210mm.pdf

Wray, S. (2020) “Amsterdam adopts first ‘city doughnut’ model for circular economy” SmartCitiesWorld. Retrieved at: https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/news/news/amsterdam-adopts-first-city-doughnut-model-for-circular-economy-519

(2019) Report: BUILDING BLOCKS FOR THE NEW STRATEGY AMSTERDAM CIRCULAR 2020-2025, Collaboration of Raworth, K., City of Amsterdam, Circular Economy. Retrieved at: https://assets.website-files.com/5d26d80e8836af2d12ed1269/5de954d913854755653be926_Building-blocks-Amsterdam-Circular-2019.pdf

Very interesting discussion of the announced commitmet to the doughnut model in Amsterdam. Covid-19, as tragic as it is, has given cities the opportunity to rethink their urban metabolism. I believe the synergy between different sectors of Amesterdam will create a new type of resilience in the city, one which will only enrich the discussion in the field of urban political ecology. It will be intersting to see how other cities might follow a similar model, and how localities in non-European countries might adapt this train of thought post-pandemic. Thank you for the insightul post!

LikeLike

This was an incredibly refreshing and interesting post. Integrated and progressive approaches to economic development are imperative as cities continue to grow, and as the climate rapidly changes. This model could be adapted to other cities around the world and guide governments in the right direction.

It certainly provides hope for the future. Following my reading of the entries within our blog, I was left quite disheartened. Ongoing environmental degradation and urban development at the expense of the environment seem to be a prevalent reality in each city. Communities have been extremely active in creating change; however, to realise significant shifts to our behaviour and activity, the government must also actively engage with society and the environment. Cities should not promote development without considering the impacts it may have on nature.

This model also highlights how Amsterdam recognises that the city and nature are inherently entwined. Therefore, future decisions and policies must strive to find a healthy balance between both the environment and the city. It is a shame that it takes a global pandemic to motivate change. However, at least it is making Amsterdam rethink their development priorities to rebuild a more inclusive, sustainable and resilient city.

LikeLike