This post has been edited and rewritten (not deleted because of companion’s comment). For the replacement post, click here.

It is particularly important to look at the way in which cities manage their water, as they are 2% of land surface on Earth, yet account for 60-80% of energy consumption and 75% of global CO2 emissions (Koop & Leeuwen, 2017:389). This puts enormous pressure on water supply, solid waste recycling and wastewater treatment. Floods are one of the most common “natural disasters” that occur in Europe, and mitigating this is of utmost importance in a country like the Netherlands; one that is constantly battling being overcome by the very water that gives them life, and their image.

The largest issue with disaster risk management worldwide is the emphasis on retroactive action: a response to something that has already happened, and many argue that it should instead be preventative. The Netherlands is a world leader when it comes to water management, but not due to their foresight. In 1953, they experienced major sea flooding which caused huge loss of life and damage to infrastructure. To prevent events like these from occurring again, the Netherlands created a Delta Programme. Under the Delta Act, the Programme has to be updated annually, and sets up a conceptual framework for research and legislation to create preventative measures.

Amsterdam’s intricate canal system is famous worldwide. Initially built to facilitate trade, now it provides recreational use for tourists and locals alike, as well as a means for water management upon which the city depends on. The city’s image is completely blue.

The ‘natural infrastructure’ of the city is built and operates through this sophisticated system of water governance, based on functional democracies, as well as including stakeholders through a “polder approach”, the Dutch method of decision making through consensus (Schreuder, 2001).

Being built on layers of peat and clay, Amsterdam has different issues to most cities in terms of water management. The city is in a constant battle of sinking into the North Sea, and consequentially being “dragged out” by citizens (Devaney, 2015). These layers of material slowly become compressed into thin layers below the surface, molded by the water seeping through.

The maximum amount the layers can sink by is 20cm before intervention must occur, as that is when surface areas become affected. The Amsterdam council tries to maintain a structure of democratic involvement, which is why there is an emphasis on community involvement in the more precarious danger zones. The people are in charge of the decision making regarding raising the areas back to their previous levels. Elected council members (similar to aldermans) are in charge of informing the citizens when, why and how their neighborhoods will be reconfigured.

The issues Amsterdam faces with water management arise from the narrative of excellency in this field that most citizens are used to. One of the largest issues to combat in their water management system is the awareness gap that could lead to complacency (OECD, 2014). This counteracts the narrative of community involvement given in the article “Raising Diemen: Amsterdam’s never ending battle against the sea”. However, analyzing multiple sources, and what I know about Amsterdammer culture, has led me to believe that there is a relatively new lack of involvement as a whole from the city-dwellers.

Amsterdammers are less involved in policy debates than before, less concerned with water pollution and development has increasingly occurred without notice of risks at different locations (OECD, 2014). Citizens also do not know what the basics of evacuation policies are, nor the origin of water, or the level of risk of the locations of their homes due to a level of trust in government that may not be appropriate.

A large challenge is that the actors who benefit from spatial development do not have responsibility over costs related to water risks. Ongoing spatial development increases exposure to flood risk. This has lead to equity issues relate to escalation of costs of water management, including those of private home owners to deal with “sinking” pavements.

Climate change poses the risk of even larger flood risks, as well as water scarcity and urban drainage that has to adapt to heavier rains.

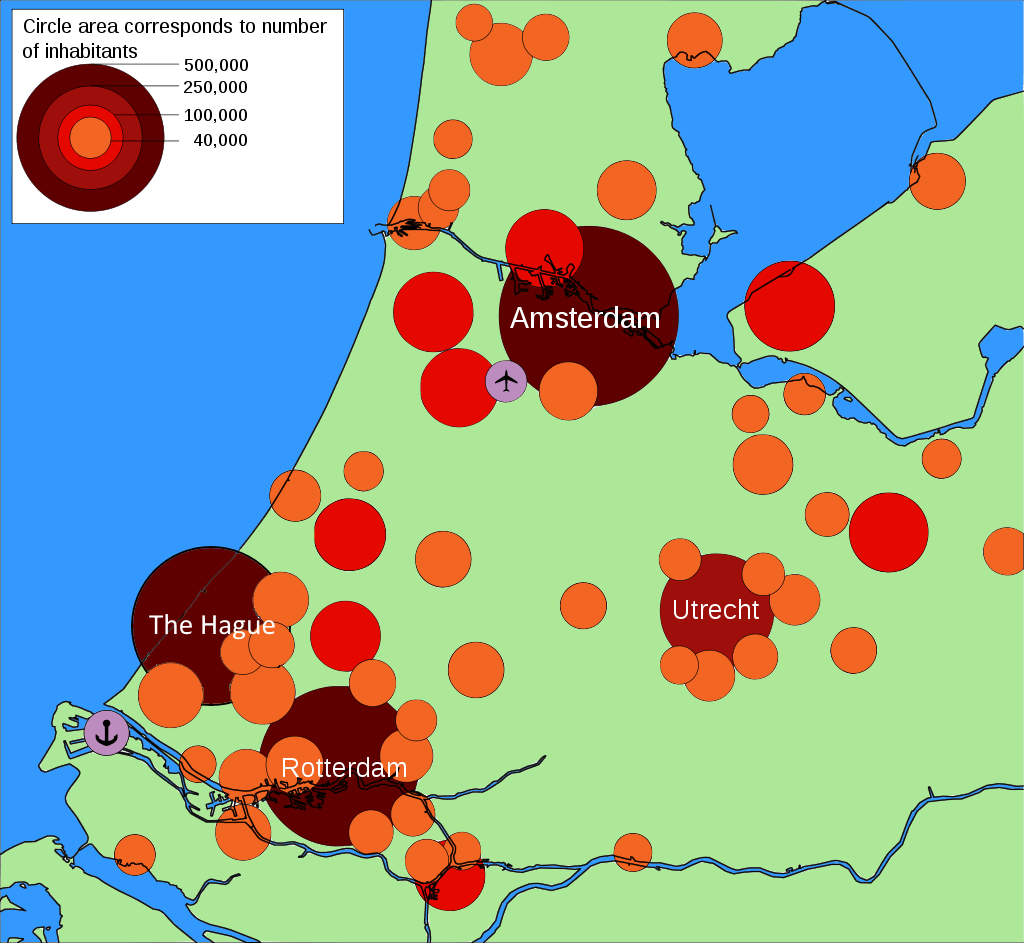

There are regional disparities in effectiveness of water management, the relevance to Amsterdam being the huge population growth in the “Randstad”, the megalopolis that it is in with the three other largest Dutch cities (Rotterdam, Utrecht, and Den Haag). What does this entail for flood safety standards? The risk gets worse in more populated areas. This also affects the speed in which the ground “sinks”- more people, more development, the quicker the peat and clay below the land compresses.

Amsterdam’s effective water management and risk assessment is one of the best in the world. But this could be its downfall. Water is in and around (and below) the entire city! The people need to fight to keep themselves updated, and with the help of the Delta Plan, this could grant them the capability of remaining on top of the steadily worsening conditions.

References:

- Devaney, B. (2015) Raising Diemen: Amsterdam’s Never-Ending Battle Against the Sea City Metric. Retrieved on 02/20/20. Accessed at: https://www.citymetric.com/horizons/raising-diemen-amsterdams-never-ending-battle-against-sea-1516

- Gawlik BM, Easton P, Koop S, Van Leeuwen K, Elelman R (eds) (2017) Urban Water Atlas for Europe. European Commission, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

- Government of the Netherlands, Retrieved on: 02/20/20. Accessed on: https://www.government.nl/topics/delta-programme

- Koop, S., van Leeuwen, C., (2017) The challenges of water, waste and climate change in cities, Environmental DEvelopment and Sustainability, Vol (19) pp 385-418

- OECD (2014), Water Governance in the Netherlands: Fit for the Future?, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing. Schreuder, Y. (2001) ‘The Polder Model in Dutch Economic and Environmental Planning’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 21(4), pp. 237–245.

Word count: 823