The concept of the ‘urban’ implies a metropolitan area with an economy centred around the secondary or tertiary sector (Pelling, 2003). Risk implies the likelihood or harm and severity at which this happens (UNLV, n/d). Urban risk is therefore thought of as the challenges faced by metropolitan areas in the wake of disasters. With the ever increasing rate of climate change and the continued sprawl of urban cities, economic and social risks are becoming more and more prevalent.

For Las Vegas, disasters can take many forms such as wildfires, droughts and flash flooding. Seismic activity also threatens the city. Mitigating the risk is key to protecting the city and its population. In this blog post I will consider the risk of earthquakes faced by Las Vegas and how the state officials have tried to deal with this

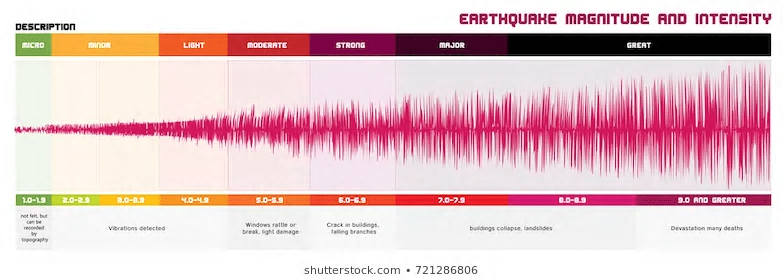

Nevada is the 3rd most seismically active state in the USA (UNLV, n/d). There are faults running through the Las Vegas Valley capable of producing a magnitude 6 earthquake. There is also significant threat from faults near to the California-Nevada border in Death Valley (Johnson, 2019). These faults are capable of producing a 7.8 magnitude earthquake. The seismic waves from this would be felt throughout the city of Las Vegas despite its distance away from the epi-centre. This is due to the rock structure of the Las Vegas Valley. The Valley is bounded by a hard bed rock and filled with soft sediment – this amplifies seismic waves by trapping them, hence why quakes are still felt a considerable distance away from the faults that created them (UNLV, n/d). In July 2019 an earthquake occurred. Its epicentre was located roughly 200 miles from Las Vegas, in Ridgecrest CA. Many of the shows in Las Vegas were stopped for the evening and viewing decks in some of the hotels were closed to inspect for damage and to protect tourists. Thankfully though, there was very little damage and normal business operation resumed quickly.

Is the significant lack of damage from a powerful earthquake due to the Las Vegas planners? – It very well could be. State officials issued building codes in the 1990s. These were made so that the Las Vegas strip could be earthquake proofed (Mullennix, 2019). For many of the builders and hotel owners going ‘over-code’ was common. This meant that the hotels went above and beyond the needed regulations. Reasoning for this is likely that businesses did not want to incur any losses and cease operation in the face of disaster, as tourists are the main source of income in the city. However, building standards are far less stringent on the outskirts of the city in urban dwellings. The majority of these homes were built just after WW2 and are more prone to damage from seismic activity. In these areas mitigation of earthquake risk comes in the form of disaster evacuation plans. Clark County have made an app that helps homeowners create their emergency contingency plan. It encourages stock-piling and the purchase and use of solar electricity storage – if power outages were caused (Maldonado, 2019). This is a similar story in many urban dwellings in the USA. Response to disasters is usually about repairing the damage in the wake of a disaster – rather than preventing the damage in the first place (UNDRR, 2019). This is due to the high cost of retro-fitting buildings to fit codes issued in 1990. In Reno – another city in Nevada state buildings are not up to code and a significant earthquake could see it destroyed as badly as Christchurch was in NZ in 2011 (Johnson, 2019).

There are calls for urban risk to be better studied to avert disastrous impacts of natural events (Schipper, et al. 2016). In Nevada this is currently happening by studying fault lines, this is aided by ever improving technology and knowledge of seismic events (Cutter, 1996). In doing so it is hoped that intervention can be strategically targeted (Avila and Wilcox, 2016).

In terms of the relation of urban risk to the study of urban political ecology, I shall break it down. Urban populations are significantly more at risk of disasters due to development and sprawl. In Las Vegas the risks from earthquakes is heightened due to the densely packed nature of buildings and the high number of people found in the city. Policy is being implemented to ensure buildings are up to standard (political) – however this is only enforced for the buildings along the strip – the area that would be economically worst hit if damage to buildings and loss of life occurred. This gives the impression that the financial prosperity of the city is far more important than the populations residing there. Despite this, earthquakes remain a relatively random phenomenon – whilst their cycles can be roughly predicted, random events can still occur. Therefore, as is the focus with much academic writing, planning for and mitigation of disasters in major cities needs to happen pre-event. Cities all too often take action in the wake of disaster – and often times this is too little too late.

Building codes information can be found here: www.clarkcountynv.gov/fire/oem/services/Documents/Emergency%20Preparedness%20Guide.pdf

Word Count: 826

Reference list:

Avila, S. and C. Wilcox (2016) Clark County structures built for earthquake safety (WWW) 3 News: Las Vegas (https://news3lv.com/news/local/clark-county-structures-built-for-earthquake-safety, last accessed 18/03/20)

Cutter, S. L. (1996). Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Progress in Human Geography, 20(4), 529–539.

Johnson, B. (2019) Is Nevada at risk for a large and devastating earthquake, (WWW) KNPR: Nevada (https://knpr.org/knpr/2019-07/nevada-risk-large-and-devastating-earthquake, last accessed 19/03/20)

Maldonado, C. (2019) Eathquake preparedness: How to prepare for a natural disaster, (WWW) KTNV: Las Vegas (https://www.ktnv.com/news/earthquake-preparedness, last accessed 18/03/20)

Mullennix, W. (2019) Can Las Vegas hotels really withstand earthquakes: top tips for quakes (WWW) Visit Las Vegas: USA (https://www.feelingvegas.com/can-las-vegas-hotels-really-withstand-earthquakes/, last accessed 18/03/20)

Pelling, M. (2003). The vulnerability of cities: Natural disasters and social resilience. Earthscan Publications. Chapter 2.

Schipper, E. L. F., Thomalla, F., Vulturius, G., Davis, M., & Johnson, K. (2016). Linking disaster risk reduction, climate change and development. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 7(2), 216–228.

UNDRR. (2019). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Distilled. (p. 28). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://gar.unisdr.org/sites/default/files/gar19distilled.pdf

UNLV (n/d) Earthquakes in Southern Nevada: Knowing the risk and how to prepare (WWW) UNLV : Las Vegas (https://www.unlv.edu/news/release/earthquakes-southern-nevada-knowing-risk-and-how-prepare, last accessed 18/03/20)

Important points raised around the responses to a natural disaster, rather than ensuring that standards of buildings, facilities and infrastructure are high enough to deal with an event. Noticeable that despite Vegas’ high level of development and standards of living that certain areas of the city are lagging behind in terms of standards and level of response, similarly to some districts in Toronto as I have found. Would be interesting to see if there’s policies focused on the wildlife and ecology of Vegas when a disaster occurs, as well as on human and economic losses.

LikeLiked by 1 person